BY MARGARET LALIBERTE, EASTSIDE HERITAGE CENTER VOLUNTEER

William Eugene Le Huquet may be best known as the editor and publisher of The Reflector, the Bellevue area’s early newspaper published between 1918 and 1934. But he was so much more than that as a tireless promoter of Bellevue, its merchants, schools, and community organizations. The initial masthead of the Reflector provided a clue to his agenda: “Non-partisan, Non-sectarian, Neutral [he later added “Non-individualistic”] A Medium for the Exchange of Ideas relative to local improvement.”

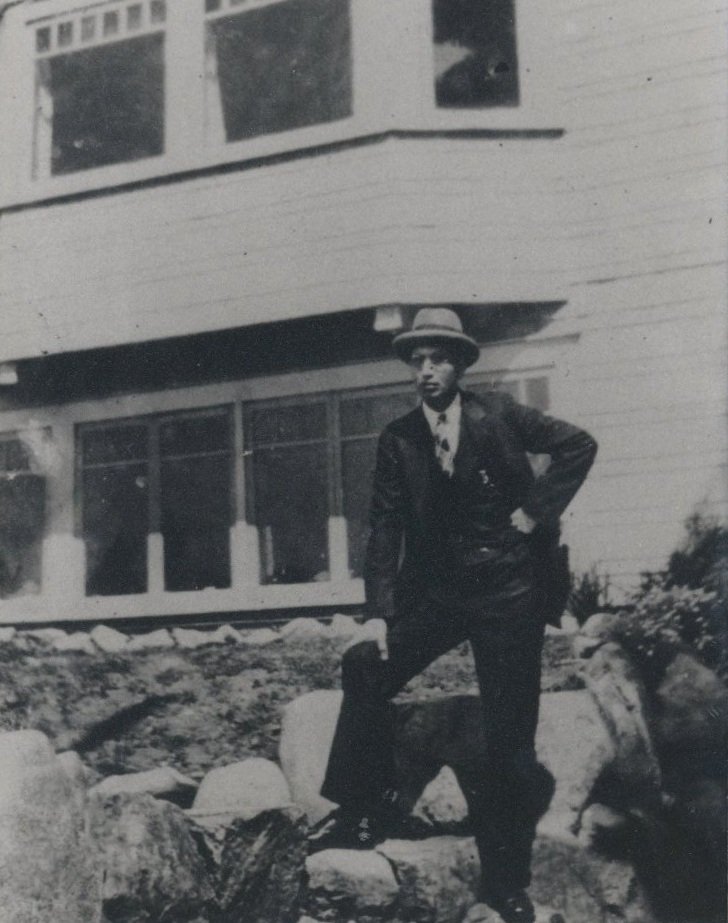

W. E. Le Huquet in front of the family home at 9616 NE 5th St. (1998BHS.16.05)

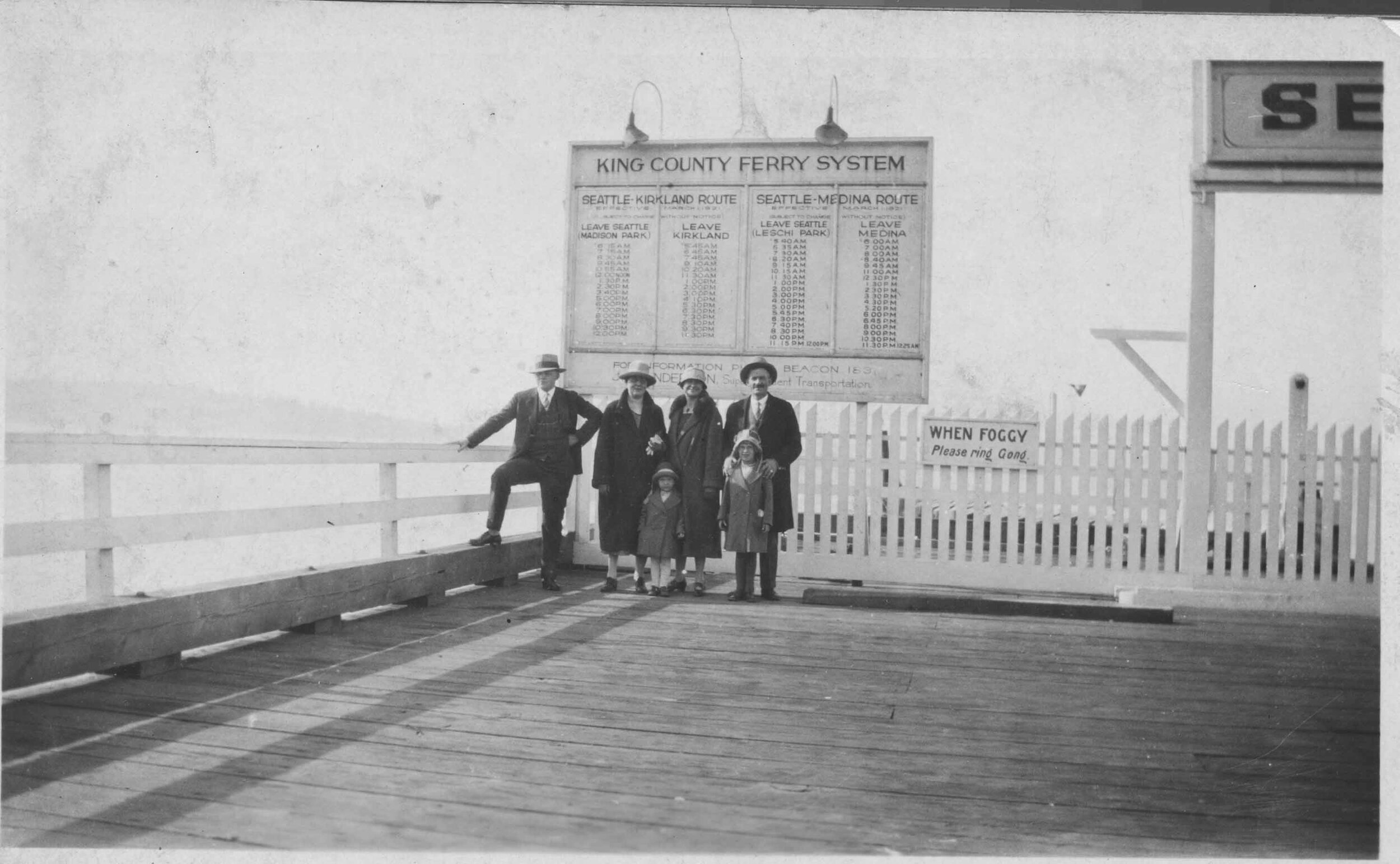

Although Le Huquet’s overarching goal was to create a vibrant community --“The greatest need of Reflector Territory is cooperation and you know it.”-- he could hardly be considered nondividualistic or neutral. He was passionate, creative, ebullient—and, on occasion, plain cantankerous. Editions of the Reflector illustrated all of those traits as he tirelessly exhorted readers to support local businesses, join the myriad clubs and organizations that proliferated during the Twenties and Thirties, support such local issues as the public ferry system, fire protection, and local school district, and vote, vote, vote. “Individual patriotism to local endeavors should be our first consideration.”

From the outset, the Reflector was a family affair, and Le Huquet invited his readers to watch and participate. January 1, 1919, his eldest child, Sylvia, made her appearance as a typesetter—at age six. “She is learning to set type to help her daddy. She set up the poem on the front page…Sylvia wishes to become an Editorette.” Over the years, as the eight remaining Le Huquet children were deemed old enough, they all joined the paper’s staff. When twins were born in December 1919, Le Huquet invited his readers to send in suggestions for the babies’ names. But just a month later he had to announce that one twin, the boy, had not survived. “Our Little Editor was born December 17th 1919 and died January 17, 1920. “

Le Huquet concocted intriguing ways to boost newspaper subscriptions. In 1920 he announced the Better Reflector Contest. Subscribers were invited to mail in their criticisms and discovery of errors. He awarded five points for misspellings; 10 for both unintentional grammar errors and “worthy suggestions.” One-half point was awarded for each cent of new advertising and 100 points for a new subscription. The winner could choose one of two First Prizes: $25 in cash or a $40 first payment on a $350 lot in the new Lochleven subdivision on Meydenbauer Bay. (Mrs. H. Anderson won first prize and elected to take the payment on the lot.) To promote both the paper and local clubs and organizations, he agreed to split the proceeds when subscriptions were submitted in a group from a club.

With nine children ultimately attending local schools, Le Huquet pushed for the development of the local school district. He had vigorously supported a school bond measure in 1920 and helped it pass with a 3.5-to-1 margin, after it had been defeated 2-to-1 in 1916. He ran for the local school board twice, was elected once and then defeated in 1927. He firmly believed that a healthy, growing school system meant a growing business district as well.

Le Huquet served as the first Secretary of the Bellevue District Development Club when it was founded in 1922. For years he screened movies for the community on Wednesday and Friday evenings at the Bellevue Clubhouse on today’s 100th Ave. N.E. (site of the Boys’ and Girls’ Club). But it was not always smooth sailing. In 1927 “Because the children attending the Bellevue Clubhouse movies do not appreciate the admission price of 10c by being quiet during the performance, the price has been raised to 15c on Wednesdays. For the present the price on Fridays will be 10c. The next move will be to omit children’s prices altogether or admit only those accompanied by parents or guardians.” The unfortunate upshot of this kerfuffle was that the following month the Bellevue District Development Club decided to cancel its sponsorship of the moving pictures program.

Somehow Le Huquet found the time and energy to run a second local business: he produced a variety of flavoring extracts under the Le Huquet label. They were sold in local groceries from Wilburton to Kirkland and in a few locations in Seattle.

Le Huquet Flavoring Extracts Advertisement, The Reflector, October 6, 1932

W.E. Le Huquet left Bellevue sometime after 1930 and moved to New Jersey, but his family remained and his wife Lilian continued to publish the Reflector. By 1933 Sylvia had become Assistant Manager, Gloria was Chief Compositor, and the rest of the clan were listed as Assistants. But in 1934 the newspaper ceased publication. By then Bellevue had a second newspaper, the Bellevue American, and the Eastside Journal was published in Kirkland. The Reflector, “circulating in The Heart of the Charmed Land” with a family of 2500 Readers in Seattle’s Superb Suburbs,” quietly passed from the scene.

Resources

EHC archived collection of Reflectors

Lucile McDonald, Bellevue: Its First 100 Years

Lucile McDonald, “Small Town Printer was Important figure,” Journal American, July 23, 1979

HistoryLink Essay 4146 by Alan J. Stein, 2003, updated 2011