BY margaret Laliberte, EASTSIDE HERITAGE CENTER VOLUNTEER

Growth on the Eastside during the first half of the 20th century was possible only because of the motley assortment of boats, from small launches to sizeable steamers and double-ended ferries, that serviced numerous docks between Juanita and Newcastle and on Mercer Island. Many may have heard of John Anderson, who built up something of an empire, certainly a monopoly, his little steamers and launches linking Seattle with Eastside landings and wharves. A story perhaps lesser known is that during that period public entities created public ferry systems on the lake. Between 1901 and 1950 the relationship between public and private groups ricocheted between bare-knuckle competition and close intertwining rife with conflict of interest, as various arrangements and systems were experimented with. The concept of a ferry system as a public utility was evolving. It fit in with the Progressive political movement popular in the state in the early 20th century, but its parameters remained unclear.

As early as 1892 John Anderson was running the ‘Winnifred’ between Leschi and Newcastle. (He was not the first or only operator on the lake.) Over the years he bought and sold vessels and eventually began building them as well. In 1900 the King County commissioners bought a ferry, the ‘King County of Kent,’ from Moran Brothers shipyards in Seattle. However, rather than operate the boat itself, within a few months the county leased it for three years to Bartsch and Tompkins Transportation Company (which operated a shipyard at Houghton that eventually became the Lake Washington Shipyards.) That decision precipitated a lawsuit; it wasn’t yet at all clear just what public ownership and operation of a ferry system ought to entail. It might be acceptable for public funds to be used to buy boats, but some groups believed the operation should be left to private enterprise. Eventually the state Supreme Court upheld the county’s contract. Meanwhile, King County purchased several docks around the lake for ferry use, beginning with those at Madison Park and Kirkland. Over the next few years it added ones at Mercer Slough, Juanita, Newport, Medina, and Kennydale.

L 75.0106b - Ferry ‘King County’ at the Kirkland dock, about 1910. She was the first double-ended ferry on Lake Washington

In 1906 Anderson incorporated the Anderson Steamboat Co., and in November of that year he merged it with the Bartsch and Tompkins company. As manager of the new company, Anderson inherited the ‘King County‘ lease along with several boats that B&T had built, owned and operated. A year later Anderson bought Bartsch and Tompkins’ Houghton shipyard and renamed it Anderson Shipyard.

In 1908 the ‘King County’ became derelict and sank near Houghton. However, the county was having a new ferry, the ‘Washington,’ built. Until it could be launched, the county contracted with Anderson to run his own boats, for a monthly “subsidy” of $300, on the ‘King County’s’ route. (This was a significant improvement for Anderson: the county’s lease for the “King County’ had provided a monthly payment of $200.) He was to run three round trips daily between Kirkland and Madison Park and charge “regular fares.” In future years, whenever the ‘Washington’ was out of service, Anderson would step in with his own boat. (Controversy continued over how much he ought to be paid. In 1911, for example, when the ‘Washington’ was out of service for repairs, Anderson charged the county $800 for the use of his ‘Dorothy’ and a scow for a month on the Madison Park-Kirkland run.)

The ‘Washington’ was launched in early May. Meanwhile the county set the new fares. Foot passengers—and sheep—each paid 10 cents one-way, car and driver 25 cents. Commuting school children got 20 trips for $1.00.

By Fall public support for the new ferry and its service appeared in the newspapers. Writers noted that fares and freight charges had been much reduced and the number of daily runs increased. One writer noted that the county had saved the bonus it would have paid Anderson for “the worst attempt at service it was possible to imagine.” Meanwhile, Anderson continued to build up his fleet of lake steamers. The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition was coming next year, and he would be ready to offer lake excursions on his fleet of 14 boats. Once the AYPE was over, he was able to buy boats that a competitor, Interlaken Steamship Co., had lost to its creditors.

2013.046.092 - Rubie Sharpe’s ticket on Interlaken SS Co, “Meydenbauer Bay Route”

1911 brought a major development: in March the state legislature enacted the Port District Act. It authorized a county’s voters to establish a local port district to develop and operate waterways, wharves, railroad and water terminals and ferry systems. King County activists, fed up with the stranglehold the railroad companies had over the waterfront on Elliott Bay, rushed to draft legislation for the September election. It was adopted, the county-wide Port of Seattle was created, the first such port in the state. Port commissioners were named who set to work to create a plan for projects and financing, to be presented to the voters in March for approval. The final plan proposed included a $150,000 bond issue for a lake ferry.

The public weighed in, pro and con. The Seattle Times and Seattle Star carried advertisements from the Bellevue Ferry Committee, a pro public ferry group formed to represent the interests of Eastside farmers, who wanted to transport their horse teams across the lake with their produce. The Taxpayers’ Economy League and John Anderson were opposed. Some accused supporters of being real estate speculators on the Eastside, just in it to benefit from increased land values. A public ferry would inevitably be a “ruinous” financial proposition. The Ferry Committee countered that the private ferry business had a death grip on Eastside farmers. It appealed to Seattle Star readers, who it claimed subscribed to the paper because it had always stood for “reasonable public ownership as a relief from private monopoly.”

Proposition 6 passed easily on March 5, 1912. The Port commissioners, who would run its new ferry system on the lake until 1919 alongside the county’s operation, commissioned a new double-ended vehicle ferry. The ‘Leschi’ was launched December 6, 1913 before a crowd of between 4,000 and 5,000 people. She could carry 2,500 passengers and 50 autos and teams.

L75.0090 - The venerable ‘Leschi’ ferried vehicles and passengers between 1913 and 1950. She had a brief second act on the route between Seattle and Vashon Island and finally ended her days as a salmon cannery in Alaska

The Port began proceedings to condemn Anderson Steamboat Co.’s dock property at Leschi, for use of the ferry run to Bellevue and Medina. The matter was finally settled in 1914 with the payment to Anderson of $20,000 for the facility.

Anderson built two ferries in 1914, the ‘Lincoln’ for the Port of Seattle’s Madison Park-Kirkland run and the smaller ‘Issaquah’ for his own route between Leschi and Newport, where cars connected to the Sunset Highway (today’s I-90) heading East. The ‘Issaquah’ had a hardwood dance floor for the evening cruises she made on the lake after a day ferrying cars. But Anderson was losing money on the ferry segment of his business. In 1917 he withdrew his last boat, the ‘Issaquah’ from the lake and, with the opening of the Ballard locks, turned to building large ships in the Houghton shipyard for the looming world war. Eastside residents immediately complained about the loss of ferry service with Anderson’s withdrawal from the scene. The Port Commission contracted with him once again to run the ‘Issaquah’ until the end of the year. Anderson sold her to a Bay Area ferry concern the next year.

By 1918 the whole state of affairs was complicated, and hardly anyone was happy. The Port of Seattle was expanding vigorously and would have been profitable had not its ferry operations run large deficits. On Lake Washington the County and Port ran large vehicle ferries between Madison Park and Kirkland and Leschi and Bellevue/Medina respectively, on the rationale that these routes connected to important public highways and roads in the area. A newspaper article suggested that neither entity wanted to assume control of a consolidated system, even though that would be more efficient. Anderson’s ‘Issaquah’ was gone now. Private interests had to try to make profitable businesses serving the smaller docks on the lake, such as Mercer Island, Juanita, Beaux Arts, etc. The Port competed in these areas as well when it had the launches ‘Mercer’ and ‘Dr. Martin’ built and placed them on runs from Leschi to Mercer Island and Yarrow Point respectively. It became virtually impossible for private interests to remain on the lake. Public opinion was divided: Some felt public ferries should be limited to the routes to Kirkland, Medina and Bellevue. Others believed the entire system ought to be in public hands, which the Seattle Daily Times pointed out would amount to a public Mosquito Fleet.

On August 15, 1918 the port and county commissioners reached an agreement whereby the Port of Seattle would transfer its two ferries and two launches to King County on January 1, 1919. The ferry ‘Robert Bridges’ ran on Puget Sound, the others on Lake Washington. The position of Superintendent of Transportation was created. When the man appointed to the post died unexpectedly within a week, the position was given to---John Anderson. Anderson named Harrie Tompkins, his long-time business associate, Assistant Superintendent.

Thus began a long period of intertwining public and private interests. Anderson as a public official was now in the position of benefiting himself as a private businessman. Initially the County leased all of his boats; in 1920 it bought them all, for $88,000. Subsequent investigations alleged that between 1919 and 1921 the County, under Anderson’s leadership, spent huge amounts on facilities and boats, repairing and repainting vessels (often in Anderson’s own Houghton shipyard). Repairs on the ‘Leschi’ alone totaled over $70,000. There was apparently some unusual bookkeeping: costs of improvements such as docks were treated as operating expenses for the current year, rather than being spread out over their lifetimes. The new waiting room constructed at a new, second Medina dock had a dance floor and was apparently used as a community center as well. Anderson maintained an office in the Alaska Building rather than in the County’s workaday facility at the Leschi dock. At the same time the seven daily runs to Meydenbauer Bay in Bellevue were terminated; the boat now left just from Medina. As the years’ operating deficiencies came to the taxpayers’ attention, some suspected that the commissioners might be deliberately creating a financial disaster in order to give them an incentive to offload the system.

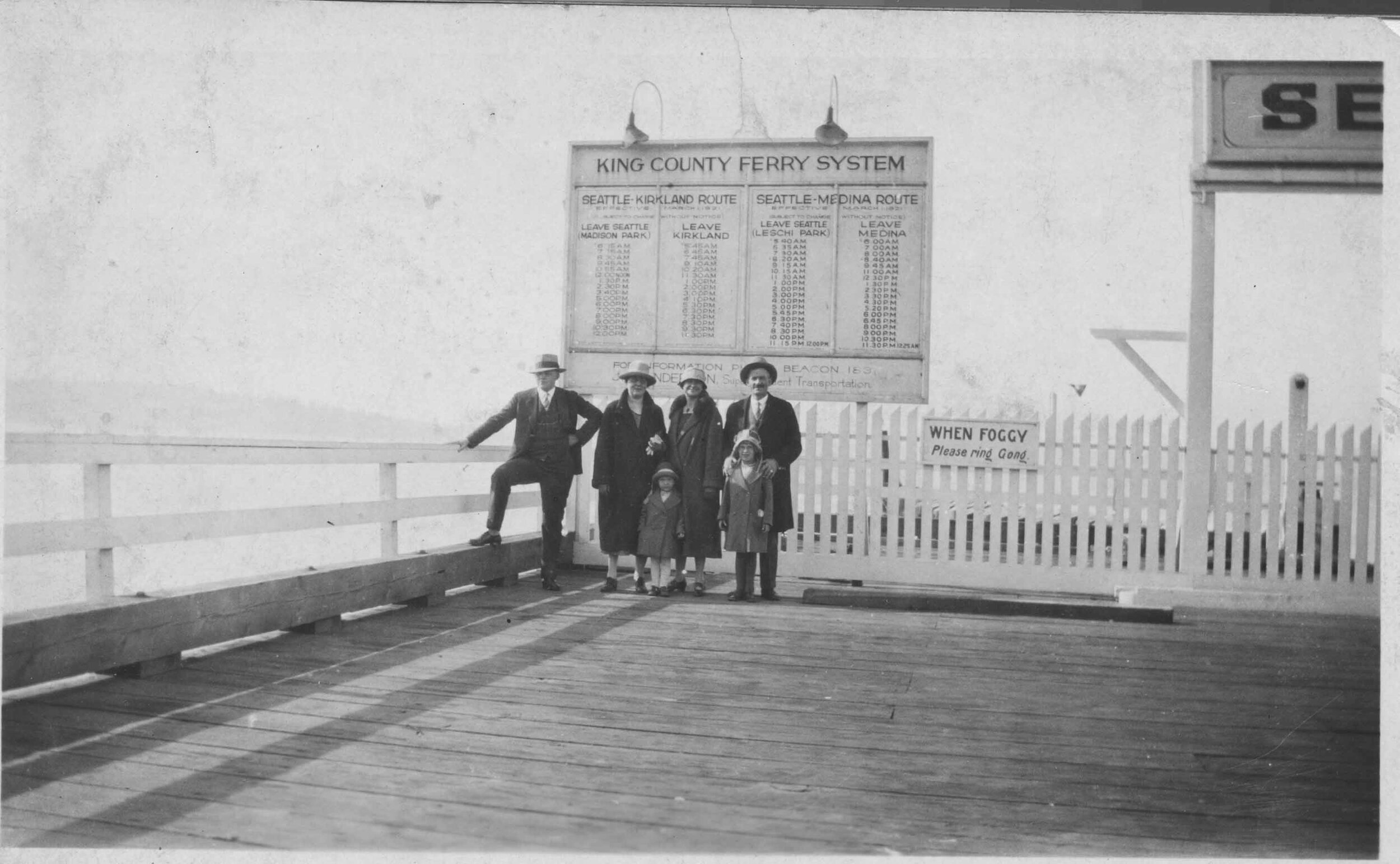

1998.02.11 - King County Ferry System. “When Foggy Please Ring Gong.” Schedule lists times for both Seattle-Kirkland route and Seattle-Medina route.

And that is just what happened in December 1921. The county commissioners leased its entire operation to John Anderson—apparently officially to a corporation called Lake Washington Ferries-- for a period of 10 years. No bids had been called for, and the whole matter was conducted almost surreptitiously. The agreement provided for no lease payments. In exchange for keeping all the system’s revenues, Anderson had to maintain routes and service and keep the boats in top condition at his own expense. He could not raise fares. But he could return boats whenever he wished. Finally, in lieu of a cash bonus for taking on the system, he was promised 20,000 barrels of oil, worth (according to some) $30,000.

The question that was in the air was, How could Anderson make the ferry system profitable when under his watch it so clearly hadn’t been? The public, particularly a Bellevue group led by Tom Daugherty, pressured the county until a grand jury was convened. Its report, after a nine-week investigation into the situation of the past several years, led to the county prosecutor’s returning indictments in July 1922 against the three county commissioners, John Anderson, Harry Tompkins, and Johnson’s brother Adolf, for misuse of county funds for three specific vessel repairs and refurbishing and for misappropriating $700 in fuel oil. Tompkins declared that the charges were “a bunch of bunk originating in Bellevue.” Defense attorney Fulton stated, “The indictments are the work of disgruntled people who have been unable to get personal favors from the commissioners.” A trial of the three commissioners was set for September in view of the November general election. Tompkin’s and the Andersons’ trials would follow.

But the indictment imbroglio turned out to be something of a house of cards. On the morning of the commissioners’ September trial, the prosecutor, in the presence of four of the grand jurors, interviewed his witnesses. (Bizarrely, one of the witnesses was John Anderson, who was to testify about the repair contracts’ terms.) To his dismay, they all either couldn’t remember having given their testimony, couldn’t recall the facts charged, or claimed now that those facts could not possibly be true. Faced with a total debacle, the prosecutor asked the judge to dismiss the three charges against the commissioners for lack of evidence. He agreed. The three still faced two indictments on repairs of the launch ‘Mercer’ and misuse of the fuel oil.

L 80.028 - The ferry “Washington” of Kirkland on Lake Washington.

While the remaining charges were still pending against all the defendants, the local media kept the affair in the public spotlight. Beginning in January 1923 the Seattle Star published a series entitled “The Ferry Deal.” It began with six brief pieces by W.E. Chambers, a former King County commissioner, who explained how the county had gotten into the ferry business and its entanglements with John Anderson. In mid-March, “in line with [its] policy to publish both sides of any controversy,” the Star had Thomas Daugherty offer his own six-part interpretation of events.

Two weeks before his own trial at the end of March 1923, John Anderson was called before the county commissioners to explain how in one year he was able to take the ferry system he had run as a county employee and, as the private lessee, turn 1921’s $234,000 deficit into 1922’s $40,000 profit and decrease disbursements by 200%. He explained quite simply that he could run the system now as a business—cut salaries, employees, unfavorable routes-- free from the constraints he had had as a public official, when “politics interfered.” (Left unmentioned was the fact as Superintendent of Transportation he had front-loaded the huge expenditures for new facilities and refurbished vessels before the commissioners turned the system over to him.)

The rest of the story ended abruptly. When the Anderson group went to trial at month’s end, the judge, after hearing all the county’s evidence and without waiting for the defense to present its case, issued a directed verdict in favor of the defendants and chided the prosecutor for having brought the indictments on the weak evidence he had. That ended the matter for the commissioners as well.

The lake ferries were now all being operated privately, although the county owned the boats leased to Anderson. In 1924 Anderson’s Lake Washington Ferries advertised daily excursions on the county’s steamer ‘Atlanta’ between Lake Washington and the Seattle waterfront through the Ship Canal and locks. Lake cruises and excursions were more lucrative than the ferry routes. In 1925 Anderson announced that he would turn boats back on the following January 1 (which the lease allowed him to do) unless the county would pay $70,000 to buy and install a new engine on the ‘Lincoln. ’ Or the county could just give him the boat and he would pay for the engine. As one wag suggested in the newspaper, maybe Anderson could compromise with an Evinrude outboard.

Anderson persevered; in 1927 his lease was extended without fanfare until 1951. But it was becoming clear that the real culprit in the “unprofitability” of ferry service was the automobile. Paving of the highway encircling the lake was completed in 1923, and the East Channel bridge to Mercer Island’s east shore opened in that year. A floating bridge between the island and Seattle had been proposed in 1921, but it wasn’t seriously considered until 1930. After funds became available through the Public Works Administration and serious planning began, one final major showdown over the ferry lease developed.

The Washington Toll Bridge Authority feared it would be difficult to pay off the bonds, which had financed the bridge, with bridge tolls so long as competition in the form of lake ferries continued. Under this pressure, in December 1938 the county commissioners cancelled Anderson’s lease. He fought back by filing a claim for anticipated damages. Negotiations among the three parties finally led to a settlement. The county would not cancel the lease, and the Toll Authority would pay Anderson $35,000. In exchange, he would terminate the Leschi-Medina route and the runs to Mercer Island once the bridge opened. The run between Madison Park and Kirkland would continue to operate.

There was one final unpleasant chapter to play out. The floating bridge opened on July 2, 1940 and that month Anderson announced that he was returning the ferry ‘Washington’ and the docks at Medina and Roanoke to the county and planned to return the launch ‘Mercer’ the following month. When the boats were returned they were found to be in very poor condition. One had had its federal license cancelled because of unseaworthiness. The commissioners ruled that Anderson would have to pay a sum, as yet undetermined, in lieu of repairing the vessels. Anderson countered that the boats were “just wore out” and that if they had been owned by a private business, they would have been “depreciated off the books long ago.” The lease, however, provided that he was to return all boats leased in good condition. Appraisers from each side were unable to agree on the present value of the boats; the county’s property agent was left to salvage what he could from the two boats.

John Anderson died of a heart attack on May 18, 1941. His widow, Emilie, and his longtime right-hand man, Harrie Tompkins, continued to operate the Kirkland ferry under the lease with the county. During World War II the ferry ‘Lincoln’ ferried shipyard workers between Madison Park and the Lake Washington Shipyard at Houghton. The ‘Leschi’ continued to make the Kirkland-Madison Park run.

In July 1947 Emilie Anderson wrote the county commissioners announcing that Lake Washington Ferries would not continue its lease beyond the end of the year and might suspend ferry service before then. But the enterprise just kept staying afloat. On January 30, 1950, however, the Seattle Times ran three photos of teary longtime passengers and onlookers—including faithful Harrie Tompkins--saying goodbye to the ‘Leschi’ on what was expected to be its final run. But no, there was still more. Members of the union operating the boat attempted to continue to operate it so long as revenues could meet wages. Their effort could not be sustained, however. On August 31, 1950 the Leschi made its truly final run on the lake, and vehicle ferry service between the Eastside and Seattle ended. In November the county commissioners voted to offer to the cities of Kirkland and Seattle the piers and land adjacent to them at their old ferry landings, for use as public parks. And so this colorful and complicated piece of local history finally came to an end.

1998BHS.027.027 - Leschi’s last trip, leaving Medina

References

Books

The H.W. McCurdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, Gordon Newell, ed., Seattle: Superior Publishing Co. 1966

Ely, Arline, Our Foundering Fathers: The Story of Kirkland, Kirkland Public Library, 1975

Faber, Jim, Steamer’s Wake, Seattle: Enetai Press, 1985

McDonald, Lucile, The Lake Washington Story, Seattle: the Superior Publishing Co., 1979

Oldham, et. Al, Rising Tides and Tailwinds: The Story of the Port of Seattle, Seattle: Port of Seattle, 2011

Articles

McCauley, Mattthew, The Era of the Double-ended Ferry on Lake Washington,” Kirkland Reporter, Aug. 31, 2001

HistoryLink Essays #9726 (Port of Seattle Commissioners Meet), #2638 (ferry ‘Leschi’ last run), #2040 (‘Leschi’ launch)

John Anderson, Shipbuilder, en. Wikipedia.org/wiki/John_L._Anderson_(shipbuilder)

Newspaper articles

Seattle Daily Times

Seattle Post-Intelligencer

Seattle Star