By Steve Williams, EASTSIDE HERITAGE CENTER VOLUNTEER

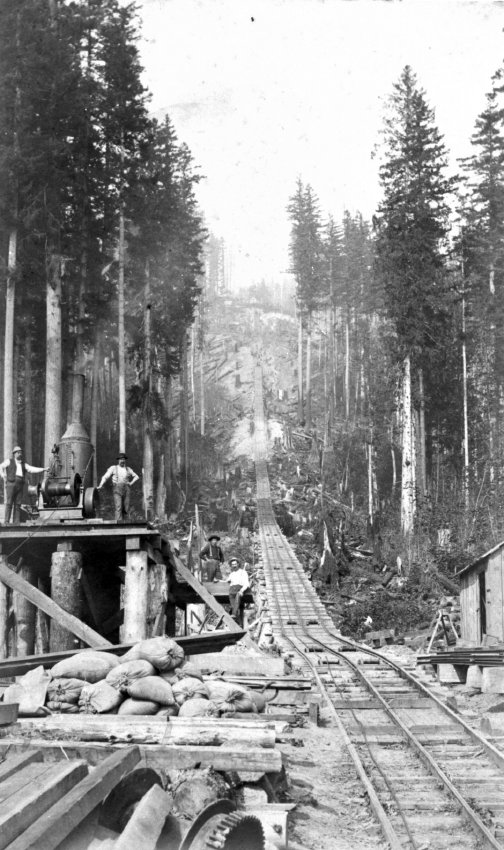

At the end of Lakemont Boulevard in south Bellevue sits a red two horse barn, five acres of pasture grasses, and the last coal miner dwelling of the 1920's town of Newcastle. For over 100 years coal was dug out of Cougar Mountain and shipped to San Franscisco, turning Seattle into a major seaport by 1880. Seattle's population then was 3,533; but Newcastle by 1918 had well over 1,000 people living right here at Coal Creek. Note the Company Store, Hotel, and Finnish miner's homes on both sides of Lakemont Boulevard in the photo below. Today the road is in the same place, but it is no longer a dirt track with transport only by horse wagons.

Photo courtesy of Ruth Swanson Parrott, c. NHS

The last coal miner in the area, Milt Swanson, lived in company house #180 there at the end of Lakemont Boulevard opposite the barn. He worked for the B & R Co. until the end of mining in 1963. For the next 30 years he hosted hikers and school groups in a little museum he established in a renovated chicken shed out behind the house. Milt had maps and tools and stories of work in the tunnels and shafts under everyone's feet. He also founded the Newcastle Historical Society and served as its President for many years. (The new 3rd City of Newcastle made him “Citizen of the Year” in 2008). He and his brother John provided tools and artifacts and stories at 15 events sponsored by the Issaquah Alps Trails Club across the street at the Red Town Trailhead.

The “Return to Newcastle” event happened on the first Sunday in June each year. It was a re-union for the miners and their families, and a chance for the trail club to introduce new residents to the woods and local trails. With help from Harvey Manning and others, those events led directly to saving Coal Creek and Cougar Mountain and turning them into public parks that are wildly popular today. Parking lots are jammed on weekends and sunny afternoons. Trails and fresh air have always been enjoyed by people; but nature and exercise have become really important to all of us in these times of Covid.

Photo by Bob Cerelli, c. NHS

Photo by Steve Williams, c. EHC

Today that historic house #180 property is owned by an outfit called Isola Homes and they are applying for permits to bulldoze it all flat and wedge 35 private houses in there between the two parks. Local citizens began a movement called “Save Coal Creek” to instead preserve the property as a wildlife crossing, a safer hiker crossing, meadow habitat, and perhaps add some trailhead parking while preserving historic features like the barn. If you enjoyed seeing the coal car in the front yard, the open pasture, and one of the last barns in South Bellevue – the question is “Will Bellevue sacrifice it all for just 35 exclusive and expensive private homes?” A public hearing is anticipated in the spring. Visit www.savecoalcreek.org for updates and more detailed information.

Resources:

“The Coals of Newcastle – A Hundred Years of Hidden History” 2020 edition, the Newcastle Historical Society, ( availble on amazon.com )

“Newcastle” files 183-194, Richard McDonald Collection, the Eastside Heritage Center

“Newcastle's Busy Mining Years” - Seattle Times article, L. McDonald, 10/04/1959

“Seattle in the 1880's” - D. Buerge, 1986 Historical Society of Seattle & King County

“14 Shorter Trail Walks in and around Newcastle” - E. Lundahl, 2018